‘Cash, Coal, Cars and Trees to keep the world to 1.5 degrees’ was the mantra at COP26. With COP27 ongoing and as promised in our ‘Turning Pledges Into Action’ blog, we consider global progress on energy transition legislation and policy since COP26.

Coal

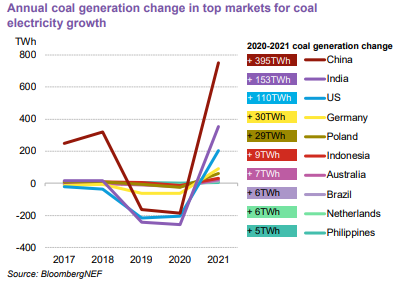

Detailed drafting doesn’t often make the headlines, but the change in the Glasgow climate pact from “phase-out” to “phasedown” of unabated coal-fired generation in the final hours of COP26 was certainly well publicised. Recent reports from BloombergNEF have shown that the advocates of the replacement wording, China and India, were (along with the United States) the largest contributors to an 8.5% increase in coal power generation in 2021.

Forecasters expect that if unabated generation using coal continues to increase in 2022, global climate targets will be even harder to achieve. The predictions highlight delayed retirements of coal generation in Europe to avoid winter black-outs and decreases in other power generation sources such as droughts reducing global hydro-electric generation, and volatile gas prices and potential gas shortages.

On a more positive note, there has been government support across the globe for reducing reliance on coal and legislative action on abatement of emissions from fossil-fuelled electricity generation has accelerated – for example:

- The US Inflation Reduction Act increases Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Sequestration (CCUS) tax credits and creates a $5bn energy infrastructure refinancing programme focusing on reducing emissions.

- Indonesia’s recent regulation on ‘Accelerated Development of Renewable Energy for Electricity Supply’ enacted a law to fast-track decommissioning of coal-fired power stations and provide fiscal and planning incentives for renewable generation.

- China’s pledge in April to “strictly limit” increase in coal consumption until 2025 and phase down from 2026. However, questions have been raised regarding legislative follow-up.

- The UK’s process for selecting industrial CCUS clusters to receive state subsidies continues despite changes in Government leadership, and beneficial tax treatment remains available for companies repurposing legacy oil and gas assets for CCUS.

Renewables

The Glasgow climate pact called upon countries to “accelerate the development, deployment and dissemination of technologies, and the adoption of policies, to transition towards low-emission energy systems, including by rapidly scaling up the deployment of clean power generation and energy efficiency measures”.

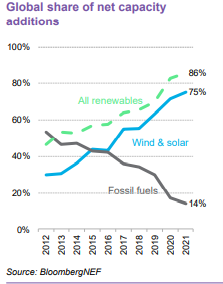

The good news on this front is that, according to BloombergNEF, low carbon generation, including hydro, made up 86% of new power generation in 2021 with 50% of that being solar. Hopefully this trend will continue although supply chain issues, particularly with the rare earth minerals needed for solar panels and wind turbines, are becoming more prevalent. The BBC’s Scramble for Rare Earths podcasts discusses this in detail including the interaction with the war in Ukraine, as the Ukrainian territories recently annexed by Russia are a key source of these minerals.

There has been little progress in actual legislation containing targets for renewable generation, with the exception being the European Commission’s REPowerEU plan, increasing its 2030 target for renewables from 40% to 45% under the ‘Fit for 55’ package, however, a range of countries have ambitious policy targets for levels of renewable generation.

Industrial and transport decarbonisation

The ‘difficult to decarbonise’ sectors such as cement and steel production, heavy road transport, shipping and aviation were not a specific focus of COP26 but there will need to be significant progress in these sectors for countries to comply with their 2030 emission reduction plans (known as ‘Nationally Determined Contributions’). Again, there has been little progress in moving numerous pledges and side agreements into legislative action. A ‘Decarbonization Day’ is scheduled during COP27 which includes sessions discussing the Global Methane Pledge, formally launched at COP26, and moving to a decarbonised fertiliser industry.

Hydrogen as a cleaner fuel (and clean hydrogen vectors such as ammonia) is a particular focus – in particular green hydrogen which is hydrogen produced by electrolysis using power generated by renewable sources. Nine countries have adopted national hydrogen strategies since September 2021, with various clean hydrogen standards emerging around the globe, but despite positive FID announcements, actual projects have been slow to progress and the IEA reports in its Global Hydrogen Review that only 4% of those in the pipeline are under construction or have reached final investment decision. The report also notes that for a global hydrogen market to succeed, strategy needs to move to policy and action – particularly to put the relevant infrastructure in place on a scale which makes hydrogen investible.

Aviation, responsible for 2-3% of global carbon emissions, adopted a long term global aspirational goal of net zero carbon emissions by 2050 at a global meeting on 7 October. ‘Jet Zero’ still remains a significant challenge, with technological innovation needed for replacement of conventional aviation fuel in addition to operational changes to lower emissions.

On the lighter transport side, COP26 focused on the transition to zero emission vehicles stating that “Road transport accounts for 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and its emissions are rising faster than those of any other sector” and consequently established the Zero Emission Vehicle Transition Council which tracks policies and targets, but only has 17 member governments and so lacks a fully global remit. As well as considering policy relating to the vehicles themselves (ranging from scooters through to trucks), the council tracks pledges relating to EV infrastructure, efficiency and greenhouse gas standards.

The energy trilemma continues and balancing environmental sustainability and energy equity with the renewed focus on energy security in light of the Ukraine war and related measures and sanctions will continue to be a challenge for many countries, particularly in Europe. For further reading, you may be interested in our blog series on how to mitigate risks on energy transition projects.

/Passle/581a17a93d947604e43db2f0/MediaLibrary/Images/2025-09-03-13-51-25-956-68b847dd1d680d7ad1a1eb32.jfif)

/Passle/581a17a93d947604e43db2f0/MediaLibrary/Images/2025-09-17-09-53-38-972-68ca85228206a7b6398617e6.jpg)